Playfullness in the arts and in architecture seems to be a gift granted only at mature age. At that age one does not have such a strong urge any longer to create monuments for one's earthly ego, but an ever increasing attraction to freely play with materials, a given program and even with the client. At the mature state in lige one comes close to being a child again, for whom after all the whole of life is play, not a temporal sequence of goal oriented jobs and actions. In addition, with childlike playfulness one doesn't become tired, on the contrary, one becomes even more energized.

In an recent interview with the editors of the Japanese Magazine Casa Brutus Tadao Ando discusses his own enduring passion in his architecture, that is, his seemingly uncountable sequence of designs for museums, churches and public buildings all over the globe. Anso-san is quoted on the interview as saying that "if he ever stopped feeling this passion he would know it is time to quit." As an example for this passion he mentions the life and death struggle described in "The Old Man and the Sea" by Ernest Hemmingway. Even though the old man in the story hadn't caught any fish for weeks, he didn't give up and finally caught an unbelievable large fish. But this catch was then stolen from him in stages by sharks. By the time he arrived back at his home port only the head of it was left. For Ando-san this story symbolically points to the importance of taking on challenges in life.

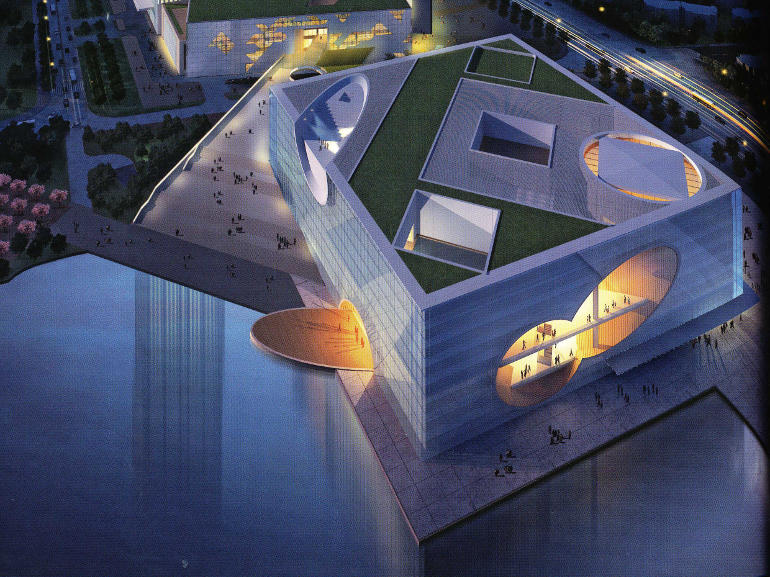

I agree, one can clearly feel this passion also in Tadao Ando's recent design of the Shanghai Poly-Theatre. One could even compare his recent output in human terms with that of F.L. Wright or Hans Scharoun in their eighties. But for me personally this is only one way to explain the sheer energy displayed in volume of his designs. Children also have such energy, lots of it, showing itself as non-ending playfulness in their creations and their behavior. But such playfulness and energy is unconscious. In a mature person it is conscious. And consciousness combined with playfullness, appears outwardly as grace, as art to us. Yes, it seems to come from the gods.

Paul Scheerbart, an European member of the first wave of Modern Architecture in central Europe has composed a German Haiku for this phenomenon. In those three lines he plays with the words "style", "play", and "goal" which rhym in the German language. This poem ends with the suggestion that an artist in his maturity shows simply playfulness in his work.

Im Stil ist das Spiel das Ziel, in style play is the goal

Im Spiel ist das Ziel der Stil in play the goal is the style

Am Ziel ist das Spiel der Stil. at the goal play is the style.

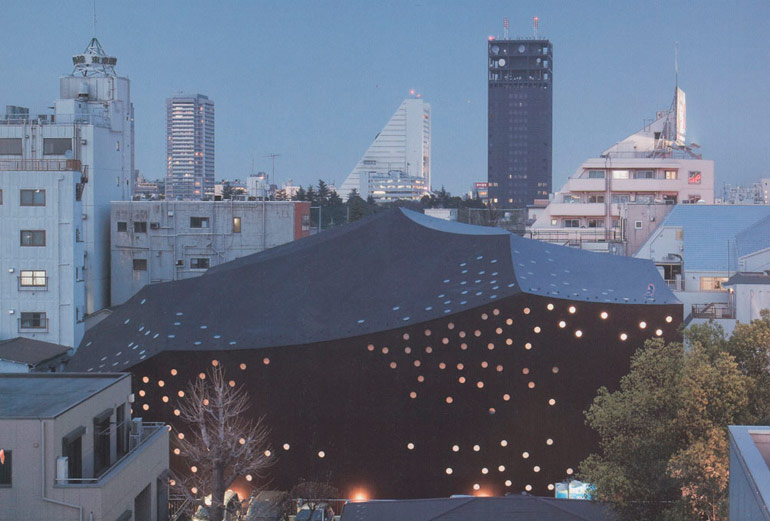

A look at the new Shanghai Poli-Theatre shows us really the form of a huge rectangular cake with circular holes as windows punched in here and there. It does remind one of the work of a child baking a cake made of sand, hardly serious in its intent. In the same sense T. Ando's Shanghai Poli-Theatre does not follow any canons of architecture &emdash; modern or traditional, Western or Asian.

For me Ando's architecture here is clearly the result of playfulness as such, which surely not by accident also befits the function of this complex, since it is a structure meant for play, for theatre, for opera.

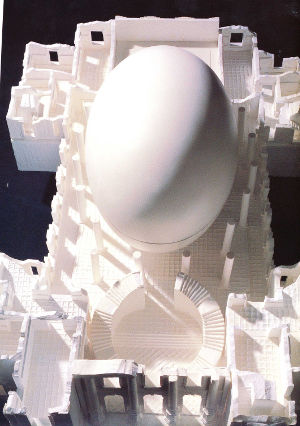

The design as a whole shows a theme which goes through the designs of T. Ando's architecture for a long time. It found its first concrete expression in the design of an "Urban Egg" in 1987 in a major redevelopment project on Nakanoshima Island, an island in a major river in the center of Osaka.

Regarding the recent history of theatre projects from the 19th century on, they were on the whole huge rectangular building blocks with a classical façade with columns initially. Consequently they went through a phase of expressing irregular interior volumes externally like in the wellknown Berlin Philharmony in the 1960's by Hans Scharoun. Finally this trend comes to fruition in Frank Gehry's designs for such architecture at the end of the 20th century in Los Angeles. I am sure T. Ando was aware of the development of of Opera House architecture in the recent past and chose his own language for such a design in our days accordingly. This form of his will surely set a landmark for the some time to come.

In size, scale and positioning it really does have only one predecessor in China, and that is the Hall of Supreme Harmony at the center of the Imperial Palace in Beijing.

An appreciation of the interior of the theatre and its immediate urban context would need a local visit planned for the future.

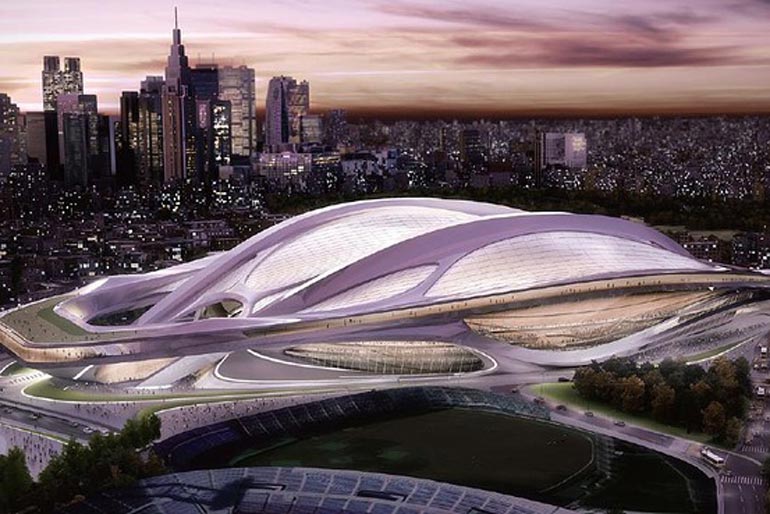

Zaha Hadid, 2012

Zaha Hadid, 2012

THE OLYMPIC GAMES IN THE PAST — The Colosseum

Since the 8th Century BC the Olympic Games were always held at the same location, in the same structures and in same nation, namely Olympia, Greece, and that at fixed intervals of four years. The hidden intention for these Games was to enforce peace every four years among the various city states which were usually at war, to worship their common Gods and to renew and reaffirm their civil ideals.

Since the internationalization of the Olympic Games in 1896 the games are still held every four years, but at different locations and in different nations, and therefore each time in completely different new physical structures. In modern times the Olympic stadiums and all other Olympic facilities are basically used only once in their full capacity. Their recent often massive and permanent architecture has often become a symbol of the national ego and pride of the host country. They are financed and also regarded as quasi national monuments.

Architecturally, perhaps all the recent Olympic stadiums have up to now unconsciously followed the paradigm of the Roman Colosseum in structure, use and gesture.

THE OLYMPIC GAMES IN THE FUTURE — The Circus

Accepting that the Olympic Games are continued every four years and in a different country each time, demands of national economics and local urban sustainability from now on suggest that the designs of all sports structures and of housing facilities should possibly be designed to be easily assembled, used, disassembled after use and shipped to the location of the next games in four years' time, or to other locations where they could be used in between.

Architecturally and economically, Olympic architecture from the 21st century on should rather follow the paradigm of the traditional Circus in structure, use and also appearance. That asks for a readjustment in our thinking about the Games generally: an orientation away from the monumental, serious, permanent and heavy towards the incremental, mobile gay and light.

AD HOC DESIGN FOR THE 2020 OLYMPICS IN TOKYO — the stadium as colosseum

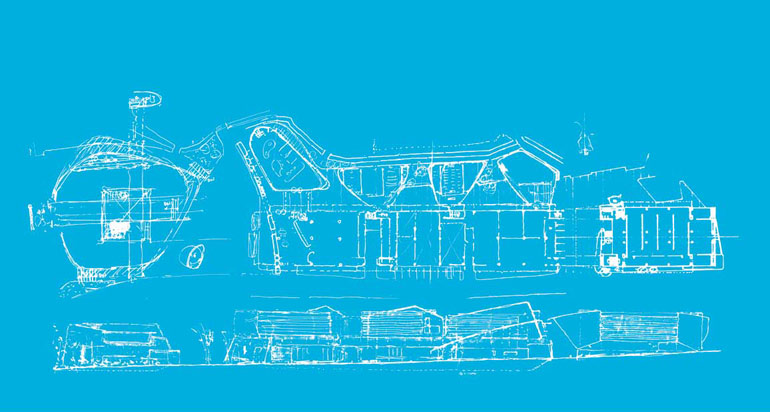

Zara Hadid's winning design in a restricted international competition in 2012 really proposes to build quasi the largest Olympic Colosseum ever envisaged. Her design, however, seems architecturally outdated and economically wasteful according to 21st century engineering capabilities and modern human sensitivities.

Concerning the economics of her proposal, her design already visually suggests probably the most expensive way to accommodate cover 80,00 visitors for the period of two weeks, and perhaps a few occasions later on. As the fate of the latest Olympics in London in 2012 and earlier ones have shown, one can expect that also her stadium, after having been used during the Olympics, will hardly be used to capacity afterwards again.

London failed to find a future use even nine months after the completion of its 486 million Pounds main Olympic Stadium. There is still no final plan for it. The International Herald Tribune in its Jan. 23, 2013 edition calls it a "White Elephant". So far the Olympic park is left empty most of the time. What to do with these exorbitantly expensive and splashy structures still frustrates the organisers of the $ 14 billion London Games and will probably do it for the envisaged 2020 Tokyo ones. One can easily infer a similar fate for Hadid's proposals for her main 2020 Olympic structures.

Concerning the management and maintenance of the stadium, her proposal gives no indication how it would create its own energy from the sun and/or other renewable energy sources as normally required by most publicly funded buildings in most economies today.

PARADIGM SHIFT IN OLYMPIC ARCHITECTURE — The stadium as circus

Theme

One should keep in mind that the Olympic Games were always meant for the celebration and joy experienced at the various unique and momentary sports events, not for the admiration of any overpowering or monumental buildings.

Hadid's proposals, however, continue to embraces an Olympic Architecture driven by an euphoric nationalistic enthusiasm, government propaganda and large-scale corporate business interests. In addition, the time has passed when a new Olympic Stadium should above all be an expression of the branded style of one individual architect. The times of architecture itself constituting above all a cultural spectacle are gone. We have learned that we have to go beyond an architecture of branding, as arisen during the modern and post-modern period of architecture, and move towards an architecture which organically co-operates with nature for our own survival.

Olympic Architecture from now on should again express a sense of communion and a desire for peace between humans of all nations, of respect for the earth as a whole and the local environment it is placed in. This would constitute a real paradigm shift, indeed.

Architecture

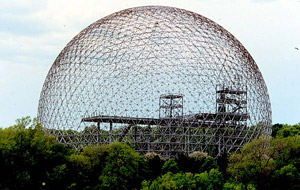

There are two precedents for our proposal. These are the prefabricated modular Geodesic Domes of B. Fuller of the USA and the various experiments with tensile roofs from Frei Otto of Germany, especially the design for the Olympic at Munich in 1998. Both present a pointer to the future.

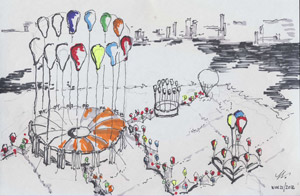

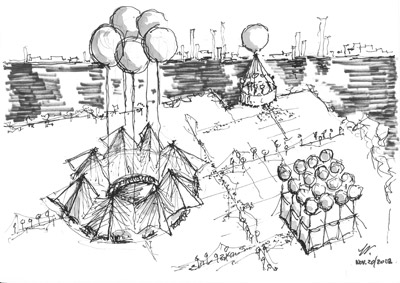

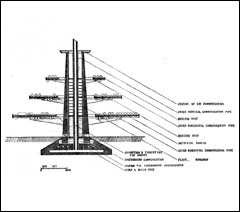

It is here suggested that the main roof for the stadium should be a lightweight tent-like structure suspended from balloons. In other words, the balloons would be freely floating above the stadium and would have to be anchored to the ground by ropes. The vast surfaces of the roof should be capable to be outfitted with solar cells to make the stadium self-sustainable in terms of energy. In that sense, not just a retractable roof, but a positive relationship to the sun would be structurally and visually established and expressed. Yes, a partnership with nature should be the theme of all architecture from now on, including the Olympic one. We envisage an athmosphere dominated by tent-structures and free floating balloons above the Olympic Grounds as such and over all of the urban background.

The substructure of the stadium should be highly modular and made of prefabricated lightweight seating easy to disassemble and to move. To allow for adjustments and variations after the disassembly according to the differing needs in other countries it would be advisable to keep the module and size of the elements of the substructure light and flexible and not build it of heavy concrete cast in situ.

Cost

Regarding the total costs of the Olympic facilities they could be shared by several successive host countries and could be spread over at least 4 Olympic Games and additional international sports events. That alone would result in an enormous reduction in costs.

After the disassembly of the Olympic facilities the spaces they occupied would again be available for other urban purposes. Thus, valuable inner urban space would be occupied and used only temporarily. Its environmental impact in the city would thus be minimized. That again would reduce the overall cost of the Games and add to their social benefits.

The design should imitate nature in its mode of operation. In nature one doesn't find vanity and waste. Seeing the Stadiums for the Tokyo 1964 Olympics being scheduled for demolition in our days and reduced to a heap of useless debris of concrete and steel, should make us conceive of all new Olympic buildings also in terms of their ultimate expedient re-use and/or disposal. Only such attitude would set a new trend for a sustainable future for our present and future cities.

From our times on, the cost of any civic architecture paid for by public money should include the cost of its changes over time, its possible re-use and final disassembly. Only how buildings are re-used in their next physical context, not whether and how they are admired by the next generation should be the main guideline of present-day architecture at the moment of design. That would bring us closer to an objective architecture, and away from the subjective architecture created by individual human egos or those of large-scale corporations. The beauty of a tree doesn't lie in any claim to fame, but in its silent contentment of being a useful and effective part of the whole in all the stages of its many physical life-cycles.

1

1

The roots of Japanese architecture

40 years ago, Gunter Nitschke introduced to the non-Japanese audience on Japanese architectural concepts, such as Ma, En, or Shikinen Sengu of the Ise Shrines. 80 years ago, Tanizaki Junichiro wrote In Praise of Shadow, lamenting the import of Western mores into Japan. 420 years ago, Sen no Rikyu, advising the shoguns Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi developed a style of drinking tea with a special architectural setting for it, which should deeply influence all parts of Japanese culture and architecture. 800 years ago, Kamo no Chomei had become a recluse and wrote Hojoki, Records of a Ten-foot Square Hut, reflecting on the ideals of a reclusive life and on the design of a mobile hut of extreme modesty after he had experienced the impermanence of all human desires and possessions in the natural and man-made disasters in Kyoto. It had become a classic for human contentment and adaptation to nature. 1000 years ago, Murasaki Shikibu wrote the world’s first novel, The Tale of Genji, when Japanese urban life and architecture came to blossom for the first time at the height of aristocratic culture. 1400 years ago, the world’s oldest wooden architecture, the Buddhist temple of Houryuji was built. Approximately 1500 years ago, the Japanese Imperial Ancestor Shrines at Ise reached the form they are still exhibiting today after 62 cyclical renewals in history.

Enduring frequent natural disasters, such as typhoons, earthquakes, tsunami, famines and huge fires, Japanese culture devolved a religion which appreciates and venerates nature directly, its forms, rhythms and energies, as felt in a big rock, an ancient tree and a beautiful or scary scenery at the seashore. Often such places would be selected for a local shrine. Thanks to their traditional mentality of seeking and practicing co-existence rather than exploitation of nature, a lot of Japan’s natural local resources, like their abundant forests, became an integral part of their architecture, both in their villages and their urban settlement.

It is, therefore, not surprising that traditional Japanese architecture, both urban and in the country, was used to be exclusively wooden. One lived in wooden buildings, one worked in such, one celebrated and one prayed in them. All of that changed dramatically when Japan started importing and imitating Western system of constructions in the middle of the 18th century and then became active participant in the Industrial Revolution with the machine in command and replacing the human hand. Changes had occurred not only in technologies but in adopting capitalism, Western education and values as well.

The influence of the tea cult and teahouse in Japanese architecture

Intimate sensitivity towards nature, combined with a sense of responsibility to the group and an appreciation for unique objects created by hands had become the main constituents for chado, the Way of Tea, which both Zen Buddhists and the samurai class supported and aactively contributed to. Perhaps the Japanese saying ichi-go ichi-e, literally, "one time, one meeting" can best describe this awareness of transience of all existence. Each encounter is unique, and one cannot re-live such moment again.

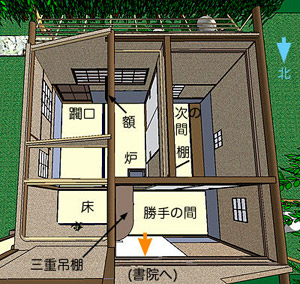

An illustration of a wabi teahouse would be Taian, which is believed to be the only existing tearoom made by Sen no Rikyu in 1582- an extremely small space of 2 mats, about 2m x 2m, built. Rikyu’s radical simplification of the tea ceremony and his reduction of its interior space to the bare minimum needed for "one sitting," was the most practical way of focusing the practice of tea on a communion between host and guests. With Rikyu, the wabi way of tea took on its most profound and paradoxical meaning: a purified taste for material things as a medium for human interaction, thus transcending materialism.

Everything in the tea arbor and in the tea garden was designed with the intention to increase the guest’s awareness. The most ordinary activities of life, such as walking, sitting or washing ones hands or sipping tea were transformed into a meditation and elevated to the status of art. He knew that the more awareness one introduces into human actions, the more graceful they would become. What was usually referred to as tea ceremony became really a meditation, and what was referred to tea room with a tea garden became a temple.

A wabi teahouse is also called a soan chashitsu, which denotes grass thatched hut that literally reflects a reclusive’s hut in the mountains. With succeeding masters the teahouse together with the tea garden underwent great changes over the ages. The tea house or room went from a completely inverted minimal interior space without windows to ever larger rooms with specially designed views out onto delicately designed garden scenery. Certain practitioners and patrons of the tea ceremony, the sukimono, kept building tea houses into their residences, or even merging whole residences completely with the ideal of tea.

Amazingly it was this rustic thatched hut, the tea house with its modest natural garden that was to release Japanese architecture from the dictates of its previous formal building tradition and usher in a freedom in general layout and utilization of materials Japanese architecture had not seen before.

Sukiya architecture

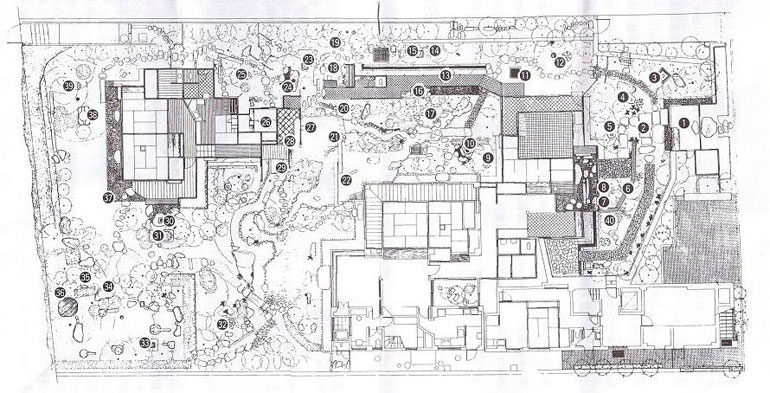

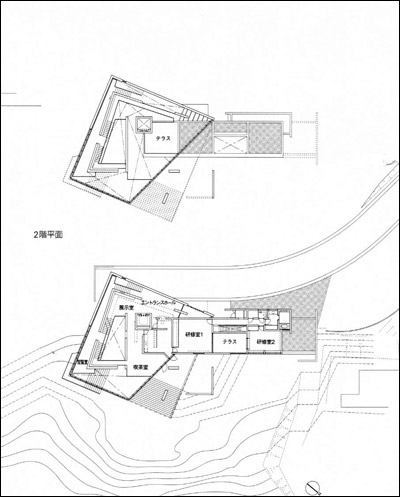

One good and relatively new example of sukiya architecture would be the shikunshien in Kyoto, a sukiya estate financed by Kitamura Kinjiro, owner of Kitamura Art Museum; it was built by the renowned sukiya carpenter Kitamura Sutejiro between 1940–1944.

8

8

Shikunshien was built over two phases. First phase included the main entrance at the far right and a long corridor on top of the picture and a series of tearooms at left. Second phase was built by sukiya architect Yoshida Isoya in 1963, shown at the bottom center of the picture. The shikunshien was designed during the recent Showa period, but still it is considered a worthy addition to a long list of classical sukiya architecture.

Through many years of internship traditional carpenters had to learn first-hand the fine sense of wood selection. They also had to balance their work with other building trades that were essential for creating traditional Japanese architecture. During the Showa period, academically trained architects began to gain recognition in Japan as heads of projects. It is no surprise that the different background of training and practice between modern architects and daiku, the traditional Japanese carpenters, or more specifically, sukiya daiku, would create a lot of tension in the design and execution of joint architectural projects. In short, carpenters learn by their hands and heart by direct touch of the building materials, architects, however, are basically trained conceptually in the head.

The traditional process of building a sukiya, or teahouse, would start with the client and the carpenter together choosing major pieces of wood from the carpenter’s own collection, such as the selection of the toko-bashira, the most important post at the center. This emphasis on the central pillar goes back to the tradition of shin-no - mihashira, central column in the main buildings of the Ise Shrines, of Buddhist pagodas, or traditional Japanese farm houses, ultimately pointing back to the worship of natural phenomena like a big tree in a forest.

Architecture based on the hand

The initial page of the website shows an example of a pair of joints by sukiya carpenter Nakamura Komuten . Today, Sukiya-daiku, as well as miya-daiku (temple carpenters) have become rare professionals in Japan who can still produce joints in the traditional and by now legendary way of creating traditional buildings that do not require nails. The traditional ‘soft’ character of Japanese architecture helps to dissipate the energies of earthquakes, a fact which kept the Temple of Houryuji standing for 1300 years. If the building method and the selection of wood is correct, wooden buildings can last for many years and continue living and breathing, unlike a steel or reinforced concrete building. Carpenters reported that they feel toxic to work in a concrete building that had been closed off for a long time, but that a wooden space would not have the same effect on them. Even a person who had spent his life growing up in a machiya, or wooden townhouse, would often speak of a similar experience.

There have been a complex systems of planting and recycling of wood in Japan until recent times when traditional wooden architecture started losing its patrons and support. Nishioka Tsunekazu, a famous miya-daiku or temple carpenter, who had lead many restoration projects, such as the temples of Houryuji and Yakushiji in Nara, was moved when he saw a hinoki, or white cypress beam, that had supported its load for 1300 years suddenly came back to life and became straight again after being freed of its load. It is a general rule of thumb that a tree that has grown for 100 years can be trusted to hold up a house for another 100 years, a tree that has grown for 1000 years can hold up a temple for 1000 years. This sense of appreciation and preservation, as well as the utmost care in handling them can only be created over many years and over many generations. Rather than just letting a tree live and die naturally in a forest, experts would keep visiting special trees and gauge the best time to harvest — preferably just before a tree was about to die naturally or started rotting internally. The wood is then processed and would live out its ‘second life’ in architecture. Inside many old wooden temples in Japan, there are often timber pieces that are over a few hundred years old or even over 1000 years old. It is tempting to think about “this piece of wood had started to grow at the time of the tea-master Rikyu” or “this piece of wood has witnessed the Heian period”, etc. It would be a shame that such wood cannot find a proper next place to live; this has been an acute problem that the wood industry in Japan has been facing since the interest in building or preserving traditional wooden Japanese architecture slowly started disappearing. These difficulties increased with the continuous change in lifestyles and building bylaws.

The few well-trained sukiya carpenters that still exist keep trying to create out new applications of their professional skills. This has been difficult since their technical expertise and the wooden materials are hard to apply in ordinary modern projects. For instance, an extremely nice piece of wood may cost more than a whole generic house, and might require a kind of spatial display that is not easily affordable by most clients. Japanese teahouses, while being one of the smallest pieces of architecture in Japan, have also become one of the most expensive buildings to build. Nakamura Sotoji, a master sukiya carpenter and his firm in Kyoto had kept on moving past their historical connection with Urasenke and expanded in building a range of projects local and abroad, including house for Rockefeller and teahouse at Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, etc.

There are a lot of other traditional artisans that a carpenter would always work together with, such as when creating mud walls or shoji screens or laying roof tiles. Traditionally, the different professions would never touch each others’ work, but younger craftsmen had started experimenting with new expressions and cross-overs in relation to their cultural heritage in Kyoto. It is hard to say what will be the future of sukiya carpentry or various other traditional crafts. Interesting results had kept emerging but unfortunately the overall architectural climate is not favorable. Lack of knowledge and interest from general public as well as architects is also a problem, besides economical issues.

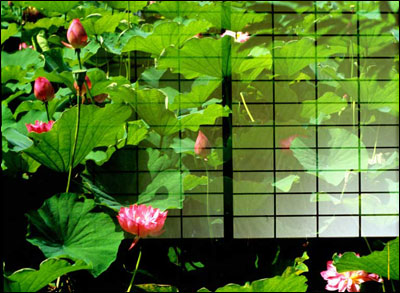

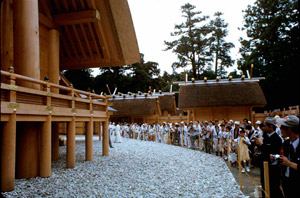

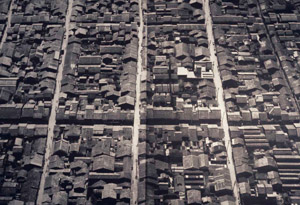

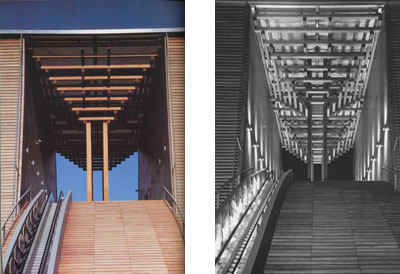

Illustrations: 1.- view from teahouse onto Katsura Palace, 2.- Old and new shrine precinct of Ise Inner Shrine in 1993, 3.- Main Shrine Building of Outer Shrine of Ise in 1973, 4.- Ceremony of offering new white pebbles in the Outer Shrine in 1973, 5.- Air view of the 1960’s: wooden urban architecture in Kyoto, 6.- Interior of Taian Teahouse, 7.- Isometry of Taian, 8.- Layout of Shikunshien, 9.- Detail of a tearoom in Shikunshien, 10.- Wooden joinery at the 60th reconstruction of the Ise Shrines, 11.- workshop of Sukiya carpentry, 12.- wooden joins of Sukiya architecture, 13.- Detail of Ryokan, a trad. Japanese inn, 14.- Interior of traditional wooden townhouse in Takayama, 15. Teahouse inside the Ise Shrine precinct.

Esther Tsoi, http://kyokoto.com

world exhibition or world exhibitionism

At the start a few comments on the the content and the overall idea of the biggest World Exhibition ever held, with a projected visitorship of 70 million people. The rather challenging theme of this exhibition "Better Cities, Better Life" against the background of skyrocketing city of Shanghai should probably be taken as an expression of the hope and dream of the Chinese people as a whole whose majority has been living in great hardship and poverty for over 2000 years. Perhaps we should call their aspirations for the 21st century "the Chinese Dream" as we have generally accepted "the American Dream" as the dominating cultural motto for the 20th century, even though the external cultural trappings of both dreams seem to be identical so far. But dreams they are both, and you have to be asleep to be dreaming, we should not forget.

With this understood, it is no wonder that despite all the hype and propaganda by the Chinese media that this show is to exhibit the latest know-how in sustainable architecture and zero carbon urban design, one is surprised to learn that all of the pavilions and extravagant installations beside the dominating China Pavilion itself will be disassembled and discarded as scrap in October after of the fair ends. Thus, this exhibition will follow the same pattern of consume and waste we are used to from previous world exhibitions. We should remember that the original idea of World Fairs was basically to showcase domestic industrial and political might and educate others on one's own culture; but this does seem hardly necessary any longer in the age of the global internet.

It is indeed sad that the community of nations even in the 21st century has not been able to come up with a more mature and rewarding purpose for a World Exhibition than basically to assemble bravour pieces of individual, corporate or national egotism at great costs to acquire the land it stands on and to relocate the residents forcefully to make room for it. The themes for those exhibitions over two hundred years have been nearly identical; I remember the name for Osaka Expo in 1970 having been "Progress and Harmony for Mankind"; these themes more or less always revolve around technological innovation and national progress with some lip-service only to a desire for human life in harmony with nature. There would have been a chance to stress this point in Shanghai by painting the whole building in green or even to change the very color of one's national flag from red into green.

Behind all the slogans stands a momentum to arouse a spirit of commercial competition to be the most advanced among the family of nations, as if there existed no real problems on earth at present, such as poverty for 1/3 of people in China, social dislocation, exploitation of the underpriveledged, ever quicker decline of the very biodiversity in China, ongoing wars and ever increasing global warming everywhere, threatening human life on earth as such.

To get once and for all out of this senseless race of nationalistic competition and of the exploitation of our resources for national or corporate gain our Institute had proposed a completely new overall approach for all future World Exhibitions, when we entered our design proposals for the Swiss Pavillon for the Nagoya World Exhibition in 2005, which was run under the motto "Nature's Wisdom", pretending to put on a green face. The main tenor of our proposal for the exhibition as a whole was that each participating nation should freely select another nation which it wishes to exhibit. In return it would be exhibited by the nation selected, so that for instance Switzerland exhibits Nepal, Nepal in return Switzerland; the USA and Russia would exhibit each other, so would Israel and Iran. I am sure every visitor to the event would love to find out how otherwise historically inimical nations see, interpret and exhibit each other. The whole exhibition would become an eye opener for every visitor. It would deepen the international, interracial and interreligious understanding between nations. Instead of a spirit of competition and national boasting it would create sympathy, good will, yes, love for each other, the visitor, the host, and the oganisers and designers.

bracketting in east asian architecture

At the Shanghai Expo probably not only my but every visitor's attention will be immediately drawn to the centerpiece of the World Exhibition as a whole, the China Pavilion, the "Crown of the East", as it was called by newspapers. It is the only pavilion fated to survive the expo to become a permanent landmark for the site as a museum of Chinese history and culture.

My immediate reaction as an architect was that I must have seen this form before, but hardly at such a huge and monumental scale. It is about 69 meters high. One's guess is that is take off from some Chinese primeval form of indigenous Chinese architecture.

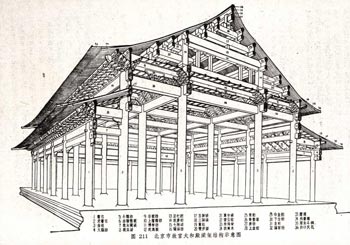

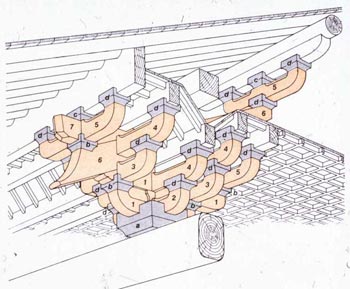

The designers state that the structure of the building is to derived from or inspired by traditional bracketing techniques as visible in most of the traditional Chinese, Korean and Japanese wooden Imperial Palace architecture, and derivative from it, in most of the religious Daoist and Buddhist architecture in those countries. The intricate system of interlocking bracketting was developed to enable huge cantilevers and overhangs for the massive roof structures of these buildings. It was repeated in structures in structures of similar size in the various gates leading to palaces or temples.

These multiple interlocking bracket structures do seem to defy gravity, and do look so simple and ordinary that one has a feeling as if those structures are part of nature itself rather than the result of human engineering skills. Even the smallest examples of these bracketing structures invoke a feeling of grace or elegance. In addition, one senses they were not created by the ingenuity of one particular individual architect but must have evolved over centuries. Admiring them, we do not bow to a we do not need to bow to a small individual architectural ego-trip, but to a collective human genius. Here individualistic architecture is transcended and becomes objective, anonymous architecture. With these braketting structures the question who was the creator of them, or when they have been created doesn't even arise. That is the hallmark of all objective art and objective architecture, they are time- and nameless.

bracketting — from archetype to protoptype and stereotype

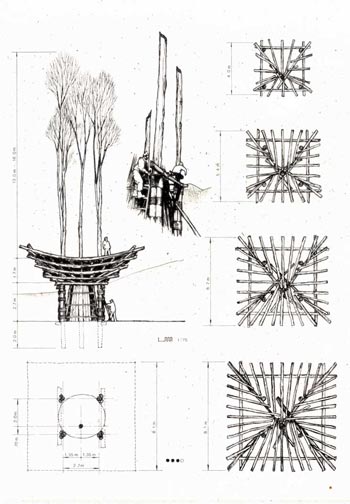

I stated before that I must have seen something like the forms of the China Pavillon even at a World Expo before. When and where? It might be slightly embarrassing, but it has been at a fairly recent World Exhibition, namely at the Japanese Pavilion by Tadao Ando at the Sevilla for Exhibition in Spain in 1992. His whole pavilion was dominated by about 15 meters high laminated wooden pillars ending on the top in a large intricate braketting system accentuated and silhouetted against a roof of translucent teflon-coated fabric.

To make huge laminated wooden columns and a traditional wooden braketting technique the central part and, I feel, the main attraction of a pavilion from an East Asian country, in that case Japan, in a country whose architecture is traditionally based on stone like that of Spain, goes beyond any individual or national boasting or egotism. One has to know that Japan up the 19th century didn't have any stonen architecture at all, only a wooden one. At Sevilla Tadao Ando "built" a modern poem on the art of wooden bracketing; in addition, his design didn't just copy or exhibit an original Japanese bracketing skill long passed, but grasped its essence and translated it into modern 20th century architectural form.

Concerning the technique and complexity of interlocking bracketing, one might want to search for an original archetype of it. The question is are there ancient structures transmitted by Chinese archeology or architectural anthropology or even still practiced nowadays somewhere in the lower traditions in East Asia which could help us to understand the tectonic logic which brought about this powerful form?

There is indeed a hardly known and rarely published predecessor of it in a ritual structure built anew annually at the small village of Nozawa Onsen in the Japanese Alps. It is, however, much smaller in scale than the China Pavilion, and it is constructed in two days, then used for an annual Shinto Ritual of Renewal of that particular mountain community and finally burnt as part of an ancient ritual action. Ref: 1.

This originally seven- and now five-stepped structure is held together by binding with straw ropes only. No other carpentry connections are used. The square building rests on four pillars 2, 70 m by 2,70 m apart with one additional central pillar, all being freshly cut trees. The central pillar is fortified with rough wooden planks and brushwood. Looking at the plans and elevation one notices of it, that the slightly curved-up ends of the bracketed platform is not at all the result of some aesthetic or philosophical speculation by early man but a result of the two edge- beams from two sides coming to be placed on top of each other at all four corners. This alone might perhaps give us a the final answer to the age-old speculation as to why traditional Chinese wooden structures often feature roofshapes curving elegantly upwards at the corners.

This temporary artifact is destroyed in a ritual mockfight which goes on over half a night. A group of young men from the village, 25 years old with lit torches try to burn the artifact while men of 42 years of age have assembled on top it and try to defend it and themselves. Naturally, nowadays, just before the whole ritual structure goes up in flames, the older men jump down to safety. It might not be on par with a world exhibition, but it is quite a show.

For our context here this ritual building might serve as a rare example showing us how bracketting was technically achieved originally, second, what the resulting overall external form of such a wooden bracketting structure looks like if one strictly followed the tectonic principles only, and forgot about secondary symbolic and purely ornamental additions.

Paraphrasing an uncomparable and immortal sentence in Jean Gebser's life work, namely "origin is always present", yes it is, but to different degrees of intensity, one would want to add, sometimes as prototypes and sometimes just as stereotypes or perverse derivatives, as seen here in the China Pavilion of 2010.

Did the China Pavilion have to be that huge to fulfil its role to represent the largest nation on the globe successfully? Admittedly, it is built in the best tradition of the Imperial Palace in Beijing or any other Architecture of Power under totalitarian rule, in front of which a human being is usually dwarfed into an ant. But size is not the issue here. Big in size does not necessarily translate into intelligent, admirable or beautiful. And climbing to a socalled "roofgarden" of the pavilion at the top, what do you look down onto the huge exhibition ground is nothing but steel, concrete and plastic. One wonders whether all of this will end into better cities and better life.

At first glimpse the pavilion does look like featuring a bracketting structure, even though in steel and 69 high; but is it? Embarassingly enough, there seems little left at the China Pavilion of the ancient skill and ingenuity, — and above all —, the elegance and grace of the art of bracketing with over 2000 years of history.

1

1

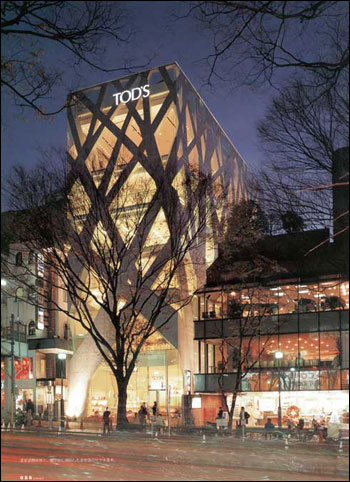

The subtitle is meant literally. Toyo Ito's just finished Za-Koenji Public Theatre in Tokyo, — black on all of its external walls and/or roof — , will undoubtedly not only absorb all of the sun' s rays shining on it, but also radiate the stored heat afterwards into the neighbourhood; it will surely become a sightseeing attraction this summer as the city's hottest spot in town. Tokyoites will be able to experience a small Urban Heat Island not only with their skin directly but also by the sight of a huge black object, i.e. by its negative Sense of Place. Pict. 1.

There is no mention in a recent interview with the architect Toyo Ito in the Japanese Shinkenchiku Magazine why he chose black for his external continuous surfaces. There are very few examples of single pieces of architecture let alone groups of buildings which are completely black; I only know of one group in India at a particular resort and therapy center. The visual effect is amazing. It has to be added, that in this case all the building are under huge trees and thus shaded and not exposed to much sun directly. Surprizingly enough, the buildings nearly disappear to human perception! Perhaps, but this is a perhaps, Toyo Ito wanted to make his building to visually disappear and not to add to the overall mess of the surrounding townscape.

And here a scientist's comment on the use of the color black: Dr Hashem Akbari, a physicist from the Lawrence Berkley National Laboratory in California, believes that by making urban areas more reflective, greenhouse gases can be offset. Also rooftops and pavements could be painted paler colours to reflect, rather than absorb, more of the sun's energy.

Unlike in earlier times, in 2009 one immediately feels tempted to ask what about green roofs which were stipulated for new buildings by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government by local bylaws already some years ago in order to counter the overheating of buildings and the annually rising summer temperatures in midtown Tokyo. Or what about green facades to balance the lack of green spaces on the ground in the inner city. Or else, what about shading devices on the facades, or provision for natural ventilation during the beautiful times of the Japanese spring and summer. One has the impression that all these important and nearly life-saving considerations for the future seem to have been sacrificed here to an apriori personal idea of wishing to create an unusual solid huge black object.

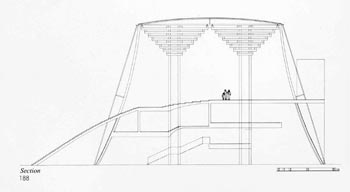

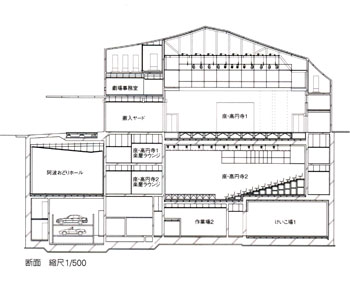

First, a few remarks regarding the structural aspects of this project. As visible on the section, one enters the main lobby and performance hall directly on the ground floor, and has to descend to a second hall in the first basement. Pict. 3.

There is no distinction between walls and roofs on this building. Toyo Ito created a single continuous surface to envelop the building. This leads to the unique wall-roof-line with a tent-like silhouette. Externally, it has its predecessor in similar tent-like looks of Scharoun's Philharmonie Hall in Berlin of the early 1960's. Pict. 2. Strangely enough and quite differently from Scharoun's Hall, Toyo Ito's main hall does unfortunately not make use of the tent-like shape of the roof also internally as Sharon did, but gave the main audience hall just a flat roof with a suspended ceiling. It is interesting, one reads in the interview with the architect, that in the early stages of the design process when he had presented a slightly different proposal to a neighbourhood meeting, that there was a general strong reaction against what was labeled a “black metal box” with a flat roof. Pict. 4. That protest motivated Toyo Ito to mold the building more in the shape of a “circus tent”, as he called it.

The metal-sheeted black walls and/or roofs are punctuated by circular windows, slightly different from the treatment visible in other recent projects. This play with circular light sources is also applied to the interior illumination devices, too. All this looks very attractive indeed, but practically, especially on the staircases, these low lights are bound to blind older people with the mildest forms of cataracts. Pict. 5.

Second, some remarks concerning the wider urban design aspects of this project. Here we come to the blindest of all blind spots in the urban architecture of Japan, both by individual or institutional architects, from the 1950's on.

The energy emanating from an isolated artifact by a single individual architect – however brilliant the design may be – will never match the energy emanating from an artifact create by a consensus of a community or by respecting and cooperating with a wider urban context. Look at good traditional examples of urban place-making in many European cities. History shows that isolated objects of corporate or individual architects' egos, or their combined ones tend to simply look grotesque in a very short time.

In the Japan after the war urban architecture consisted mainly of OBJECT-MAKING; in Japan's highly competitive and self-conscious society all these separate objects in an urban context come to neglect and reject each other mutually. Japan also created very few examples of the second stage of architectural sensitivity, that is, of SPACE-MAKING, where the inner and outer spaces of a project are given equal attention and design effort. The spatial Kakophony of Shinjuku in the center of Tokyo adds up to not more than a haphazard staccato of individual monuments to corporate greed, each one trying to outdo its neighbour. One would be hard-pressed to point at postwar examples of modern PLACE-MAKING in Japanese urban contexts like there existed in Japan's traditional urban environments.

Third, finally, a few remarks concerning the ethical aspects behind this type of architecture in our times, and in Japan in particular. Obviously the practice of architecture has always been and is more than a professional occupation for mere personal profit and reputation; I believe, it has indeed a strong ethical dimension, too. We have arrived at a point in human history where nature itself starts teaching us that the exploitation and consumption of natural resources has its limits, limits already visible on the horizon. Go to Beijing and try to enjoy a single day of unpolluted weather.

Responsibility for continuing global warming and environmental deterioration lies also with present private or corporate architects and urban planners; equally with socalled professors and educators at the architectural departments of our universities, one should add. They all together are the main form-givers of our present built environment intellectually and in terms of form. After forty years of teaching at such departments I have to confess, I have not seen one department which seriously teaches design techniques and planning strategies to prevent global warming and waste management. After all Co2 is a waste product, and a very costly one.

Every newspaper by now nearly every day carries an article of doom on the subject of climate change. All this seems to fall on closed ears with living Japanese architects who are mainly busy with individualistic and anachronistic bravour pieces in the Beaux Arts tradition and who manage to turn a deaf ear to that voice of the earth itself.

Listening to all the information and warning about climate change one realizes that everything in architecture has to be rethought and redesigned up from the doorhandle and the watertap onwards, but not for decorative purposes or as expression of individualistic artistic whims, but for reasons of human survival in an age of ever increasing global deterioration due to excessive CO2 emissions from our buildings, factories and means of transport. How buildings are heated, ventilated and cooled will have to be radically reviewed together with their structural design to ultimately measure up to a zero carbon environmet. Even the car industry has finally gotten the message, why not architects and construction firms. The age of subjective art and architecture, an architecture of waste and vanity, has to come to an end. A new awareness about sustainable design of our urban enviroment has to be born among our citizens, the planning and architectural profession, and last and most importantly, the educational institutions at all levels. Let us remember all of us are sharholders on and of this planet.

Architect Toyo Ito's latest design was not singled out for any personal reasons. It just stands representative of what has been termed here an urban architecture of waste and vanity . Perhaps, the concerns voiced in this context could be applied to 95% of other pieces of architecture by other socalled modern Japanese architects. After years of inaction and after years of denial, I plead to all of them to use their tremendous architectural and professional skills to incorporate the latest technologies to reduce greenhouse emissions and to use clean energy and waste saving devices in order to protect our environment, transform our economy, and to build a sustainable future even in cities.

Architects not voluntarily promoting and applying our recent knowledge about the threats of global warming and increasing environmental pollution, should be held responsible for it by the community. It is, for instance, already legally impossible in Germany to even cut a soingle tree in your garden arbitrarily without having to pay a penalty for it, equal to the costs for the replacement and raising of a new tree for it somewhere else.

Japanese society will soon probably be forced to use legal means to reduce CO2 emissions(1), to use renewable energy sources(2) and energy saving structures (3), as are increasingly enforced in European countries. Architecture in this country has to confront climate change headon like the car industry was recently forced to do. A governmental oversight commission could work as a whatchdog organization to decide whether a new project follows or brakes the new laws of design for a sustainable environment.

Energy hogs like the building discussed here, could be forced to have to pay a special “carbon tariff” which reflects its excess of allowed CO2 emissions and its unused chances for the production of renewable energy; incentives and tax brakes could have the same effect, postively speaking. If it doesn't cost anything to emit CO2, it won't change behaviour. One could also imagine a second state examination on subjects of sustainable architecture and urban planning being required for general architectural licensing. In the UK a socalled Green Building Council already called for a code to set targets for a zero carbon enviroment including energy, waste and water performance. According to this code all new or existing buildings would have to undergo environmental impact performance checks.

Perhaps, something like an open revolt against our present usual wasteful urban architecture and their creators might be necessary. A similar revolt is presently taking place in the medical realm in the USA. A new proposed law , Bill 1478, in the State of California would require doctors by law to provide patients with information of alternative methods of healing heart disease, the killer number one in the US . If this bill was passed then doctors in the future would be legally bound to tell their patients that there are methods like diet, exercise and therapy which can successfully cure heart diseases for next to no expenses, which their established high-tech methods can not. This would end the present useless medical tortures and expenses heart patients are made to suffer in order to line the pockets of doctors, medical universities and health insurance companies. The result would be that the State of California could save billions of dollars in medical expenses every year.

We need a similar revolutionary law guaranteeing the construction of sustainable architecture, and we need to create an architectural profession which is bound by law to create it, like we have laws enforcing the construction of earthquake resistent buildings already. Unsustainable architecture could be taxed out of existence.

In my vision, — given a different attitude in the architect — the Za-Koenji project could very well have become a community theatre with the same facilities and for the same money, but in the form of a terraced green oasis within the existing context of concrete structures, where kids and their mothers would choose to play during the day.

Possibility of an Architecture without Ego

In Japan’s architectural post-postmodern and economic post-bubble era, a period starting with the first decade of the 21st century, Japanese cities by now present a staccato of banal and repetative concrete or glass boxes, minimal or overdecorated, small or huge, low-rise or stacked high into the sky resulting in a townscape which has been basically designed by the same mind-set which gave birth to the first phase of modern architecture. With a single book, — namely Architecture without Architects published in 1964 — , Bernard Rudofsky reduced the majority of the artefacts of the Modern Movement to nothing but a huge mind-trip.

That by itself was quite a feat accomplished by one person, but unfortunately not very inspiring or helpful for the future. His book remained a collection of exotic and nostalgic images of an Age of Innocense, because it missed an important point: however much we may be attracted by such images of a more primitive way of building, we cannot go back in evolution. All the stunning pieces of indigenous architecture from all over the world he had collected as proof for his main thesis, did in fact have architects — admittedly, not in the sense of present-day architects academically trained to selfconscious “artists”, but of traditional skilled builders and artisan-carpenters.

At present, we are more and more surrounded, invaded, yes, often mesmerized by an architecture, which could be summoned up as grotesque outputs of the egos of relatively few brand name star architects. To extend or better correct Rudofsky’s indirect critique of the Modern Movement we here propose a plea for the need of an “Architecture not without Architects”, but of an “Architecture, yes, with Architects, but Architects without Ego”.

The architecture of this new group of architects does already exists but it is neither well recognized nor well published. We are too much dazzled by the present propaganda of globally spread super-structures — here I refer to both corporate offices, hotels or museums all designed seemingly without financial limits, and also to the anonymous trash of consumer architecture. So far a term proper or catch phrase for this new type of architecture is missing. What I am hinting at here, is an architecture without ego as against an architecture of unsustainable consumption, mere vanity and pure waste.

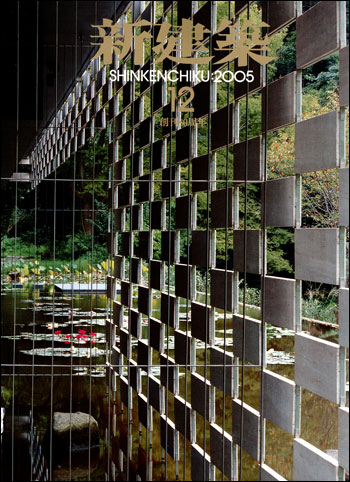

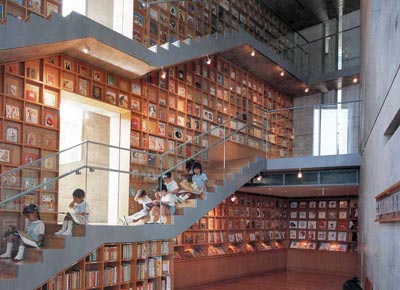

Prof. Kiyokazu Arai`s two recent extensions to the campus of Seika University in the north of Kyoto, could easily be counted among this new category of an egoless architecture which, by the way, does not mean an anonymous one. It definitely does not belong to the well-known common breed of post-modern and post-bubble architecture of Japan any longer. Arai sets the stage to an architecture which has a new character; to me it exhibits simultanously a formal and structural language globally applicable, and on the other hand, it reflects something of the traditional Kyoto townhouses, a type of ‘vernacular’ Japanese architecture close to Rudofsky's “the Architecture without Architects”

When we encounter it we do not feel like reacting to his architecture emotionally as we do to the new anonymous mess in downtown Kyoto, Osaka or any other Japanese city, nor do we feel like being forced to having to admire or praise it like any of the latest architectural stunt acts or emblems of present-day materialistic culture as visible in Dubai, Beijing or Hongkong. We pass or use his buildings quietly without being disturbed. The outside of the buildings is more hinting at the work of a refined artisan than brand-name architect of our days. What a relieve! And still his architecture is unique and new. Where are the traces of the ego of the architect here, one askes.

The design problems we confront today in the Age of Globalization are not so much related to a choice between an architecture of ever increasing universal global character versus an architecture of local sense of place, — to paraphrase Kenneth Frampton concerns —, but to a choice between an architecture of, or without ego, — and here I include the ego of individual architect as well as corporate and national egos.

It is questionable whether absolute energy hogs like the national TV tower in Beijing or other bravour pieces of skyscrapers and corporate headquarters — notwithstanding their dominating political and economic power in our societies — should uncritically be accepted as the most important visual landmarks of our urban silhouettes. Should an architect just play the role of a hore in the process of environmental abuse, or ever increasing cycle of our throw-away culture and hunger after aesthetic novelty?

Our world is slowly converted into a life of Hungry Ghosts of Buddhist lore with ever quicker rates of production and consumption of anything glittering and new, and ever less feeling of any contentment. Mankind relax, one wants to wish to ourselves! Look at nature, there everything is constantly new, individual, original and ever refreshing. Not even two fallen leaves are the same.

We seem to have forgotten, the truly new seems to arise automatically whenever there is freedom from the xerox-copying machine of the ego, and that not only in architecture. The truly creative mind, — neither struggling simply for novelty nor being enslaved by a nostalgia for the past will forever play the role of a hollow bamboo, — to use an ancient Chinese metaphor.

Taking up what I mentioned about a certain quality of non-ego in Arai's new buildings and a reference to — not at all imitation of — the Kyo-Machiya, the traditional Kyoto urban dwelling, he admitted in an informal interview to two main strains of inspiration: one is related to the actual physical site of Seika University which gently winds itself up a valley in the northern mountains of Kyoto. Arai wanted to follow that movement presented by nature itself with his new buildings. The site came with certain restrictions in terms of height, color, and roof-form, since it is part of the fuchi-chiku of Kyoto, a special preservation zone of green encircling the north, west and east of the old city of Kyoto. So the buildings had to be low.

The other inspiration has come from the structure and spatial delicacies of the traditional urban dwellings in Kyoto. There are the latticed windows and verandhas which constitute their facades and in reality very efficiently filter light, air and visibility. The “modern” latticing of the facades of Arai's buildings towards the road — even though very different in scale, material and color, does indeed give the campus now something of the architectural quality of Kyoto's traditional machinami or streetscapes.

Another characteristic feature of the traditional Kyoto townhouses are their narrow interior courtyards, the tsubo-niwa. The space requirements of the program for Seika's departments of Manga, Visual Design, Hanga and Western Painting were so large, that the buildings became too deep for enough light and ventilation. This led Arai to incorporate interior courts, somewhat narrow and high, for the lower part of the complex, prodiving a highly conmplex sense of place within the buildings. The slightly odd shapes of the buildings beyond this chain of interior courtyards, that is, on the side opposite the street, become individual structures of their own, with facades suggesting buildings higher than they really are.

This double inspiration brought about a pleasant break with the conrete boxes with holes as windows, which is the basic building type of which Seika Campus abounds so far.

Whether Arai's buildings live up to recent new standards of a sustainable and eco-conscious architecture, in terms of carbon emissions and renewable energy, is clearly beyond this appraisal here, but his architecture would surely grow even more on us if it had been incorporated.

Obviously, Arai's architecture will not establish a new style, here provisionally termed an “Architecture without Ego”, with one stroke but it introduces an exeption into our time which seems so mesmerized by what here was called the international brand name architecture. It re-kindles one's faith in the architect as a socially conscientious professional and skillfull artisan.

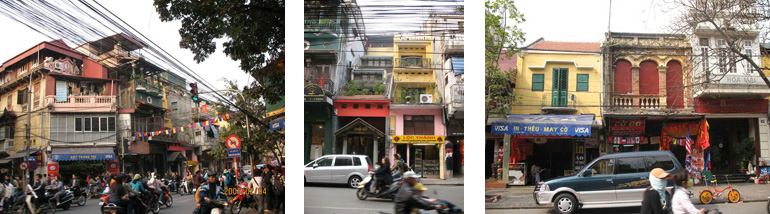

The above view of Halong Bay — a UNESCO World Heritage Site — summarizes Vietnam of today: unspoiled scenic beauty, low-tech architecture and slow-speed boats, all managed by an honest communist effort to come to terms with an invasion of a global economy.

Since ancient times Hanoi has been a city structured by lakes and rivers, plenty of urban green and surrounded by an area of loosely interwoven trade villages. Hopefully Hanoi will not learn from the models of the modern Western city-planning nor imitate modern Western city-center redevelopment with its centripetally increasing building height and population density. So far, Hanoi has carefully preserved a urban structure and growth pattern in the form of a inverted pyramid, with lowest height of buildings in the center and density and height increasing towards the perimeter. If this pattern could be retained, strengthened and translated into architectural poetry, the whole modern planning world could learn from it.

Hanoi can be roughly described as a city in three layers. The central area of Hanoi is formed by the huge Hoan Kiem Lake and the original old 36 Streets or Quarters towards its north, laid out around the 13th century. The buildings stand mostly on very narrow deep plots from two to five stories high. The succeeding layer is characterized by rather wide tree-lined boulevards, surely one of the golden eggs French colonial rule left behind. These boulevards have wide pedestrian sidewalks, and their 19th and early 20th century architecture is very European in flavour, but built on far wider plots; they often have front gardens. On the whole one is not oppressed by too much architectural ego, so to say. The buildings are mostly from five to seven stories, naturally with the exception of modernist towerblocks like Hilton Hotel. The outmost third layer is marked by more recent and rather haphazard growth around ancient villages.

One gets a taste of this outer zone on one’s approximately one hour’s drive from the airport into Hanoi: first right and left just finished huge, but flat industrial estates of international enterprises, then through suburban villages with a lot of street life and a type of building similar to that in the original center of Hanoi, equally on a narrow sites of 3–5m width but often 30m deep, with a strange 4–6 story high building, facing the street, and all of them, having a roofed open verandah on their top. If there is a common architectural denominator to indigenous or regional Hanoi architecture, then it is this type of building. It follows you on your drive from then on right up to the old 36 Quarters of old Hanoi.

The developing countries in East Asia, and therefore also Vietnam, try to survive in a very schizophrenic context in the moment: one the one hand they themselves wish and they are pushed internationally to develop as quickly as possible, — and that is the carrot side if the situation; it is speeded up by the massive influx of international money; on the other hand, they are urged not to pollute their environments and use sustainable development policies in industry and architecture and urban planning. And that is the stick of the present situation. The developed societies warn them from their own recent experience against further pollution and unsustainable growth, but simultaneously crave their cheap labour and build up manufacturing capacity. The West’s expectation and pressure for ever more and cheaper goods and simultanously for responsible and sustainable environmental behaviour is plain unreasonable, useless and ultimately self-destructive; pollution of the air and water doesn’t stop at regional or national boundaries any longer.

Strolling through the Old Quarters north of Hoan Kiem Lake one realizes suddenly what Lawsonification has done to our central city, Japan included. These centrally computer-controlled and externally architecturally identical garagelike stores for groceries and other daily necessities, — Lawson, 7 and 11, and others — open twenty-four hours and staffed by part-timers in shifts, have practically eradicated the old pa-and-ma variety of groceries and to a great degree monotonized streetscapes of our inner cities. In old Hanoi this old variety and complexity of multi-use architecture mixed with owned housing still exists. Naturally, one could easily miss the noise and danger of the ever-present motor-cycle, or have at least their exhausts cleaned up; but the motor car would probably destroy the whole spuke even quicker. Perhaps, and this is my fear, this unique architecture and atmosphere nursed by the very owners of each plot will probably disappear here fairly soon, too. It would be a pity if it were replaced by the common Mori Hills formula of Tokyo’s Roppongi district. Yes, Mori does claim his redevelopment schemes of super high-rise architecture contain diverse urban functions and uses, but all at one point on top of each other, designed and controlled by just one huge financial outfit, and ultimately owned by some anonymous shareholders who sit in Florida or on the Bermudas.

There should be no misunderstanding, I am not suggesting to enshrine the architecture of these old 36 Quarters of Hanoi, far from it, I suggest to learn from it in a social and architectural sense. No modern academically trained architect today could or even would want to continue the complexity of this street architecture, created by the thousand hands and minds of the anonymous dwellers there over a couple of decades, yes, centuries. It is true critical regional architecture marked by a subtle balance between the social, architectural and economic goals and needs of a particular society. More than urban architecture, it is a kind of urban nature. It has grown over a long time, and it constantly renews itself organically, even though in very small steps and jumps. But I wish to emphasize that everyone from this globe who travels to Hanoi today will end up next day in some coffee or restaurant or boutique of the old city. It has a transnational and transracial attraction.

Development of the individual human or of whole cultures mostly occurs in three stages: it starts with an urge to fulfill basic material needs, like food, shelter and love, and is followed by the urge to satisfy aesthetic needs such as, with cultural luxuries and pleasures which come with riches and power. Spiritual needs mostly — there are exceptions in history — arise in the human being after the fulfillment of the previous two. Neither individuals nor civilizations can probably take a shortcut, even though — as we witness in East Asia in the moment — the speed of material and aesthetic development seems to increase exponentially in recent history. Spiritual voices from the East Asia are mute so far.

So, for the Westerner, going to Hanoi makes us aware of what we have lost in our cities, and what we should help the Vietnamese to treasure, keep and nurture.

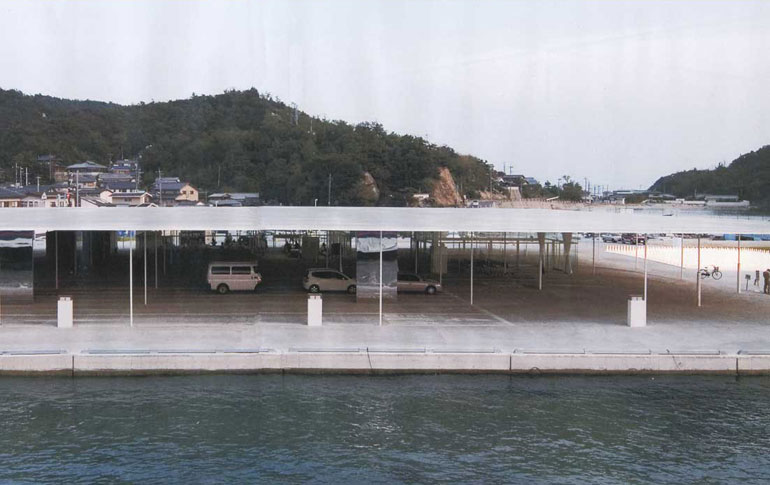

The Harbor Terminal built in 2006 on the Island of Naoshima surely reaches a climax of an already well-discussed fashionable wave towards ever more lightness, brightness, transparency and insubstantiality in Japanese architectural design, especially in the life work of Sejima Kazuyo and Nishizawa Ryue. Functionally, here on Naoshima one large “super-flat” metal roof covers a ticket office, a waiting hall for ferry passengers, a souvenir and coffee shop, and a flexible event hall, and in addition, provides ample space for casual parking.

As for modern product design, one feels that a similar climax in minimalism had been reached by a steel table, 9.5m long, 2.6 m wide, made of a single prestressed 3mm thick steel plate, which rested just on four legs on its corners. It was the brainchild of Ishigami Junya, a young architect from Tokyo.

Yes, both structures even though at different scale are light and thin alright, but do they convey grace? Or do they simply remind us of a magician’s floating or levitation act?

The trend towards lighter and more diaphanous structures in human architecture and product design started ages ago, it did not coincide with the rise of the modern movement in the early 20th century, nor is it presently just a fashion in Japan. Perhaps it does not appear just accidentally at this point in wider human history. It can be understood as an unconscious artistic expression of a particular stage in the evolution of human consciousness when it developed a growing awareness and desire to express transparency. In an essay meant as an introduction to a Japanese Design and Architecture Exhibition at the Lousianna Museum of Modern Art in Copenhagen in 1995, I had introduced Jean Gebser’s, a 20th century German thinker’s unique vision and interpretation of human art and architecture which has escaped the notice of architectural awareness so far. In his life’s opus which he had called “Origin and Present — Foundations of an Aperspective World — Contribution to a History of the Growth of Consciousness”, he links the evolution of human material and behavioral culture to the growth of the evolution of human consciousness, and that from its most ancient past up to now: he interprets this evolution as a process from an archaic, via a magic, a mythic, a mental to a transparent phase. According to him the archaic phase showed the human being still very much in unison with nature, in the magical phase there appears a first emergence of an awareness of a self differentiated from nature; in the mythical epoch an early verbal mind is developed, and at the mental phase of evolution, basically our modern time, the human being acquires a fully fledged ego in opposition to his body and nature as such. In the fifth, or what Gebser called the integral phase of evolution, the human being experiences wholeness, unison with everything. To Gebser this means that from here on the previous levels of consciousness have become transparent to the human being. He argues that this “integrating diaphanization” is the central feature of human consciousness to come, even though this “future” has probably started already with the birth of Gautama Buddha.

Naoashima: superflat

Naoashima: superflat

Does this increasing inner sense of unity, transparency and lightness perhaps also express itself in an urge to make our external creations also lighter and more transparent? Should they become more graceful? Yes, definitely, but to be precise not in a sense of levitation and ultimate disappearance but perhaps more in a sense of grace balanced by gravity. To illustrate what is meant here by balance of gravity and grace, and by transparency in some of the best human design, here an image from ancient China — also just a roof floating over a viewing spot in Guilin, and an image from Japan — the interpenetration of rooms in a traditional Japanese townhouse in Takayama, a transparency achieved without the use of glass.

No doubt, to recognize and/or create true grace, you will have to be of that fifth stage of consciousness yourself. It can’t just be achieved by a couple of formal tricks or by magic. On this earth, — however much we may pretend in our creations or behaviour — we will never defeat gravity. And there is nothing perverse about weightlessness in space, but there is here on earth. Yes, recent space and rocket technology will influence our creations here in our architectural forms. These forms will not just be childish but definitely an expression of a change of consciousness.

Grace we find best at the two extremes of the immense spectrum of consciousness, in the realm of the unconscious, — a flock of cranes dancing — , or at the other end, in the superconscious or the holistic, — a Buddha statue, sitting on the crest of a lotus flower — perhaps the only image of a human being truly sitting and grounded, but nevertheless floating, a perfect balance between gravity and grace, no tricks.

Admittedly, such balance is difficult to enter into internally or to build externally. But the best of human creations have made it visible throughout the ages. The two above structures — the terminal and the table — don’t show a victory over gravity, but quite to the contrary, a fight with and cheating of gravity; gravity cannot be overcome in the physical body in a physical universe. A table seemingly floating in mid-air is a magician’s trick, so is an absolutely flat roof, only 15 cm thick. These architects belong more to the guild of magicians than builders. They don’t work with gravity, like for instance, a spiders web or a suspension bridge does, they work against it. They only fox the eye of the beholder.

Ishigami Junya: magic table

Ishigami Junya: magic table

We can make poems or build but intimations of a balance between gravity and grace. In other words, we can “dream” about it, build substitutes of it. That is our tragedy as humans, we can intuit the real, — a sense of unity, a sense of global wholeness and grace, but we do and live only a substitutes of it in our various cultures in history — that’s what human culture ultimately has been and is: a substitute for what we really want and what are truly capable of achieving. Look at man’s latest attempts to reach the sky, in Beijing, in Dubai, New York or Paris, to mention only the names of places rather than those of their designers: we fake, not show grace.

In summary: we may ask, is the Naoshima Terminal a structural bravour piece? Yes, definitely, but it surely does not disclose how this roof — looking like a sheet of white paper — is actually be held up.

Is it an architectural bravour piece? Visually, it comes close to the equivalent of a architectural floating carpet of Arabian magic tradition. Functionally, open on all four sides, it probably fulfills its required program; experientially, our critique with such post-Miesian openness and glassiness is: you approach it, you see it all and at once, and there will be nothing else left to discover and conquer the next time.

Is it an environmental or ecological bravour piece: hardly. One has the feeling that this building can hardly sustain itself energetically, forgetting about it producing extra energy. If public works projects can’t be build environmentally and ecologically more friendly, and energywise more sustainable, then which projects will be?

The basic difference between Sejima’s Naoshima terminal building and the traditionally Chinese roof structure quoted here is similar to that between a fakir standing on one leg for hours or days and presenting an image of tension and stress, and a yogin who sits on a posture of utmost ease — and thus emanates ease to the viewer, too.

The human being — in his own body and in his creations — has always been and always will be struggling with the “Disease of Time”, that is impermanence, decay over time and finally exstinction. From a Western biblical perspective one could say that the human being is punished for his original sin by the disease of time. Never again after the “fall” has the human being been at ease with time. Deep down he realizes that time cannot be healed, however, he discovered very early that it can be renewed. “Time flies, as they say — or time renews itself as we would say”, Prof. Tiwari from Nepal added to his New Years wishes last April.

Here a view of the Karesansui or Dry Landscape Garden of Ryoanji, a Zen Temple in Kyoto from April 2006. Present scholarship places its origin approximately into the middle of the 15th century. The designers and their intentions remain basically unknown. But Ryoanji, like no other extant traditional Japanese garden, has become a new paradigm of landscape design in modern times all over world, and even in Japan itself. In a strange sense it survives by ever more clones and permutations.

Closer looks, however, reveal that this garden must have recently undergone a major facelift which no Westener would have expected, or if he had been asked , would not have easily condoned. Not only was the roof of the surrounding wall furnished with brand new shingles, all the rocks were washed down and thus denuded of their admired patina and very small and subtle moss which had settled there over hundreds of years and thus had become part of their particular beauty to us. As one discovered in the process of cleaning it wasn’t simply moss, but Lichen, a symbiotic combination of two life forms, algae and fungi, that had covered the rocks and was slowly splitting and dissolving them. (1)

When the rocks were washed down and freed of their accumulated layers of dust and parasitic growth, what re-appeared was not something like the ‘original face’ of those rocks, the archetype “rock” as such, but just their hypothetical face as of 1450. Who knows whether the stones were not covered with some moss already at the time when they were actually set into the garden? Their original color and structure will irretrievably be lost.

The recent restoration in Ryoanji has nothing mystical, religious or ritualistic about it. It was just some partial repair or restoration within the garden, as is usual in the architecture and gardens of the West, too. It was a purely physical act. After some time this restoration will have to be done again. By restoration, aging and decay, the disease of time, cannot be healed. Time will ultimately win. In this context it is notable that in India the name of the all-loving and all-devouring Goddess Kali derives from the Sanskrit kal meaning black, time, and death. She is a personification of the disease of time in East Asia.

Here a few famous examples of such repair and restoration work Japan: Katsura Detached Villa was completely disassembled and re-built from 1976 to 1982, even though every visitor nowadays will be told that the present form is that of the middle of the 17th century. The much admired machiya, or wooden Kyoto townhouses, have always been subject to ravaging conflagrations in history and were quickly replaced, not as strict copies of the old ones but with reasonable adjustments and alterations. In more modern times, the Metabolists, a group of Japanese progressive architects in the early 60’s used the very recognition of different life or decay cycles of human beings and man-made artefacts, — combined with different scales of building operation in modern times —, as the main structuring feature for their own urban design proposals in the last half of the twentieth century.

Modern Japanese preservation policies of traditional single buildings or groups of buildings are out of tune with this traditional practice of restoration, repair and exchange. The reason is, that these laws were based on European strategies and policies of preservation; but those were basically meant and formulated for stone buildings, and not for one- or two-storied wooden ones as existed in Japan up to the mid-19th century.

Time might not be able to be healed, but the human being from early on discovered that it can be ritually renewed. Probably mostly unknown to the rest of the world but in actual fact rites of renewal are still very pervasive in contemporary Japanese culture. They inform the very form and content of Shinto liturgy and its ritual behaviour. The biggest rite of renewal in architectural terms is the shiki-nen-sengu, the renewal of the Imperial Ancestor Shrines at Ise at fixed intervals, i.e. every twenty, or originally, every 19 years. About 15, 000 Hinoki trees, all about 200 years old, will be felled for this re-construction of the overall 115 sanctuaries. The cutting of the first tree for the sixty-second renewal has been performed again this spring, naturally in utter secrecy and at night.

It is officially one of the most ‘sacred’ ritual acts in the process of renewal as a whole — but in fact, it consists simply of the felling of two trees which after eight years will become the shin-no-mihashira, or, “the sacred pillar of the heart”, or in Western terms, “the holiest of holies” within the two sanctuaries. They will ultimately be buried underneath the reconstructed two main buildings of the Imperial Ancestor Shrines; one of these is dedicated to the deity of the sun, the other to that of food. Even for us in the 21st century the two deities could easily stand for the two most important energies sustaining human life on earth, sunlight and food. And adequately enough, these two “deities” are venerated in the form of a tree, reminding us of its sacred role in supplying us with oxygen to survive.

During this eight year long rite of rebuilding absolutely everything is going to be renewed, all the buildings, fences and gates, all the deity treasures and decorations inside the buildings and, last not least, all the thousands of white river pebbles spread in the precinct. The sight and smell of the renewed shrines confirms to us the strange paradox we require from the sacred object, it should always look very fresh, but simultaneously, be of the most ancient possible form, be beyond time as such, be something like ‘the original face’ of a sanctuary as such.