|

|

|

Based on the above citizen’s initiative and the following survey report of 1972, the Sanneizaka Area was designated by the City of Kyoto in 1976 as a ‘Preservation District of Groups of Traditional Buildings’. Later that year it was selected for the national register as well, now recognizable by the suffix of jūyō, i.e. ‘important’, in front of the term as a whole.

Right from the start the preservation plan did not envisage a complete restoration to some kind of golden age or original state of the area, as was the case with Tsumago, a posttown in Nagano Prefecture which was selected for national register at the same time as Sanneizaka. Instead the city of Kyoto instituted a form of mutual consultation, architectural guidance and financial support the moment an owner asked for a building, rebuilding or repair permit. Therefore, the renewal and visual restoration of the area would follow a speed determined by the actual owners in the area themselves. It was accepted that the preservation of this townscape did not have to mean the mere protective freezing of a particular historic architecture; instead it was intended to be used as positive planning tool, intimately related to the economic development of the district. In the past in big Japanese cities, rebuilding of townhouses after major fires was undertaken while respecting overall regional architectural characteristics, social class distinctions, and available technical expertise. Builders also worked within the framework of a clear vocabulary of commonly accepted structural plan and facade elements.

These very attitudes produced the now much-admired unity we experience in traditional Japanese townscapes. The City of Kyoto, as part of its preservation strategy, issued a 17-page manual, a short form of the architectural history and visual quality of the original preservation report. In it the city government suggests six types of facade treatment, in elevation and section, to be respected in any repair, rebuilding or new construction within the area, as well as, the mechanism for financial subsidy for such work by the local and central government. The preservation strategy does, however, not impose any restrictions on the spatial or functional design that occurs ‘behind’ the regulated facades. The plan, however, does provide regulations regarding height of buildings and roof-treatment.

The six types of stipulated Machiya facades in this area are:

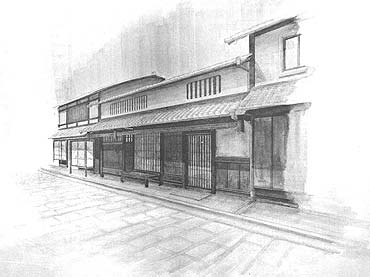

- Machiya with mushiko or insect-cage windows in the clay walls of the suppressed second floor; they are already depicted on screens depicting town-scenery of Kyoto of the Muromachi era of the sixteenth century. They can be used as dwellings or shops with dwellings. (picture A)

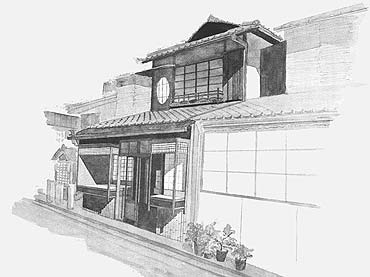

- Real two-storied Machiya flourishing from the Meiji era onwards. It also has two alternatives: as dwelling and as shop with shop-windows combined with dwelling. (picture B)

- The modified two-storied Machiya, appearing from Taisho times onwards; it displays just a touch of Kyoto’s delicate Sukiya architecture. It also comes in two versions, as mere dwelling or as shop-cum-dwelling with shop-windows to the street. (picture C)

- Machiya in Japanese mansion style, often with a large second-floor gable of a hipped roof peeping over a boarded-up mud-wall with formal gate.

- The truly Sukiya-style Machiya, designed in the spirit of wabi-sabi of tea arbor style architecture. (picture D)

- The Ishibei-koji Street Machiya, which as a group were added to the Sannei-zaka Preservation ensemble only in December 1995, stand on premises surrounded by decorative tall stone-walls. They were mostly built during the Taisho period.

|

|

| Four types of facades stipulated by municipal preservation strategy for purpose of repair or restoration |

|

|

|

| A |

|

B |

|

|

|

| C |

|

D |

|

|

It should not be forgotten that the ground-floors of many of the Machiya here are used to sell souvenirs or traditional local pottery.

In addition, the preservation strategy contained concrete suggestions for the proper visual restoration of fences, walls and gates, as well as, the paving of the walkways. Basically, in cases of simple rebuilding or repair, no major problems arose in persuading the owners to follow any of the suggested six facade styles in consultation with the city planning departmemnt. Difficulties arose with the construction of completely new buildings or the reconstruction of buildings which had been built more recently, and thus belonged to none of the listed six categories in the first place.

This might be the place for a general comment, that Japanese national and local preservation ordinances make a distinction between two types of preservation projects:

- shūri, ‘repair’, defined as the repair or rebuilding of part or the whole of the facades (about 1 m in depth) of existing historic buildings within a designated Preservation District.

-shūkei, ‘visual restoration’, defined as reconstruction of a building or parts of one, in harmony and style with the general spirit of a surrounding ensemble of valuable historic buildings; here belong structures in concrete, bricks or cheaply plastered steel structures which are mostly of more recent date.

In the first case, the owner is entitled to a financial subsidy of four-fifth or 80 percent of the cost of the facade; in the second case, two-thirds of such expenses are subsidized. In 1996 the city supported approximately ten cases of repair and restoration together per year, and that because of budgetary restrictions. In all “important” preservation districts, such as Sanneizaka, the subsidies are supposed to be equally shared by the central and the city government. Restoration, however, is never subsidized by the state, since it recognizes its duty to preserve existing important cultural assets, but not to visually uplift a bad environmental situation. In addition, tax incentives or easements treated as tax-deductible contributions do not exist. For 1997 there was a budget of 70 million Yen available as joint municipal, prefectural and state subsedies for all four ensemble preservation districts in Kyoto.

In order to get rid of existing eyesores and to restore what one could call the architectural integrity of any special architectural ensemble, the preservation district as a whole, as described before, was split into eight small sub-zones of 30-50 m length, each with their own dominant architectural style and ambience. Persuasion was then used to ensure that new constructions or major reconstructions blended into the prevalent architectural character of the smaller preservation units. But it was always silently accepted that urban design here would also have to reflect visually any major changes of life-style, as it had traditionally done in this area in the past. Thus, it was absolutely necessary for the owner, the builder and city planning officials to deeply understand the historic and architectural integrity of the particular zone involved, and to be able and willing to reinforce its architecturally and socially desirable sense of place. Any new building should relate as much to this sense of place as it should to any particular architectural style. Otherwise, one felt, the place as a whole would deteriorate in terms of visual attraction, and thus also, land-value.

In fact, this strategy proved to be very effective. As comparative photos of the city government’s pamphlet on the district clearly document, with each addition, repair or restoration the area has gained in overall environmental attractiveness. An ever-increasing flow of tourists has definitely widened business opportunities. Only 2 percent of the people owning property there have sold it in the course of the last ten years. Tradition definitely ‘sells’ in Kyoto. That proves that designation as a historic district does not necessarily means a drop in land values. During the last ten years, 35 percent of the new constructions in the area have been shops and restaurants, 65 percent have been dwellings. Despite commercial success, it has remained a desirable place to live, too. The reasons are manifold: the area has preserved much of its green within its boundaries; it has good traffic connections with other parts of Kyoto; and the chances that there will be construction of buildings higher than two stories in the near future are slim. In fact, half of those who own businesses in the Sanneizaka District also live there.

All the above figures are part of the surveys which were published in 1979.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Traditionnal treatment of facade |

|

|

|

|

In 1997, the time this article was written, the situation didn’t look that rosy any longer. At present, with no further demographic surveys at hand, I wish to quote a city planning official who characterized the condition of the district as becoming less and less an area to live in, that is, only houses with commercial use have recently been repaired or rebuilt, not pure dwellings, and as an area with mostly elderly population, and in addition, living in single occupancy houses. In other words, the area as a whole slowly turns into a commercial district. Many building sites stand empty.

An interesting side-effect of the designation of Sanneizaka is that local citizens, their architects and carpenters had to relearn and reacquire various skills used in traditional wooden construction; these skills were just in danger of disappearing. To be able to revive local carpentry skills, and to instill trust in these crafts on the part of the citizens, is indeed no small by-product of the effort to preserve any particular historic district.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|